Last Updated: 2021/02/11

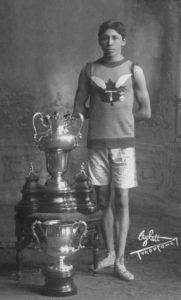

Tom Charles Longboat, born “Cogwagee,” was a renowned long-distance runner. He grew up on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Ohsweken, Ontario, and was a member of the Onondaga Nation, one of the six Indigenous nations that constitutes the Haudenosaunee or “Iroquois” Confederacy spanning portions of modern-day Ontario, Quebec, and New York. In the early twentieth century, Longboat ascended to world’s-best status in distance running. His talent and celebrity forced observers to reckon with the success of an Indigenous athlete in a sphere that influential imperial powers aimed to reserve for white men. Longboat’s legacy is celebrated in Canadian and Indigenous circles alike, as well as in elite running circles beyond Canada.

Tom Charles Longboat, born “Cogwagee,” was a renowned long-distance runner. He grew up on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Ohsweken, Ontario, and was a member of the Onondaga Nation, one of the six Indigenous nations that constitutes the Haudenosaunee or “Iroquois” Confederacy spanning portions of modern-day Ontario, Quebec, and New York. In the early twentieth century, Longboat ascended to world’s-best status in distance running. His talent and celebrity forced observers to reckon with the success of an Indigenous athlete in a sphere that influential imperial powers aimed to reserve for white men. Longboat’s legacy is celebrated in Canadian and Indigenous circles alike, as well as in elite running circles beyond Canada.

Longboat was born on July 4, 1886, the second child of Elizabeth (Skye) and George Longboat.[1] He had two siblings, Lucy and Simon. His father died in 1892 when Longboat was still a young child. Though his father’s death greatly impacted the family, it was in Longboat’s youth that his talent and passion for running initially bloomed.

In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the Canadian government forced thousands of First Peoples families to send children to residential schools to receive Western educations, adopt Christianity, learn English, and practice skillsets and vocations deemed “civilized” and appropriate by the State. The government leveraged these powers with parliamentary legislation, most directly the Indian Act in 1876. An 1884 amendment allowed the government to forcibly compel Indigenous children to attend school. Longboat was enrolled at the Mohawk Institute Residential School when he was around twelve or thirteen years old. Enduring accounts of Longboat’s childhood suggest that on two occasions, he escaped school and ran to various family members’ homes for cover. The second escape, to an uncle’s farm, was successful. He did not return to school, and began laboring on farms and regularly commuting to jobsites on foot.

He started racing in regional events and played the sport that came to be known as lacrosse (which originated among Indigenous communities in North America). He placed second in a five-mile race on Victoria Day in Caledonia, Ontario, in 1905. He won that race in 1906. He also won a 20-mile “Around the Bay” race in Hamilton, Ontario that year. Hamiltonians tout this race as the oldest road race on the continent, and it was already popular and prestigious by the time of Longboat’s victory.[2] He trained at the West End YMCA in Toronto on an indoor wooden balcony track. He raced and won a short YMCA event in preparation for the renowned Boston Marathon, which would become one of his most celebrated performances.

A record-setting performance in Boston bolstered Longboat’s career in 1907. He gained the lead and began extending it by the midway mark, ultimately winning the race in 2:24.24. This time beat the standing record in the premier running event by about five minutes.[3] After the race, the Boston Globe reported that “never before in the annals of running, either amateur or professional, in this country or abroad, has Longboat’s performance been approached.”[4] He reportedly finished the race with a fast kick, broad smile, and in good condition, despite the cold and rainy weather. Such a high-profile victory elevated Longboat to stardom in the Western running circuit. That summer, he set a new Canadian record for five miles when he raced (and just beat) a three-man relay of his countrymen.[5]

His fame and dominance in the sport earned him many nicknames that stressed his speed and also his race: “The Indian Iron Man,” “The Streak of Bronze,” “The Onondaga Wonder.” Some names invoked Indianness through popular stereotypes. For example, “The Speedy Son of the Forest” infantilized Indigenous men and drew on the trope of noble savagery—an image of Indigenous people as primitive creatures of the natural world, incapable of surviving or participating in modern society. These misguided titles represented a central paradox in the lives and careers of not just Longboat, but any famous Indigenous athlete or public figure: they simultaneously experienced praise and racism. Papers depicted Longboat as silent and stoic, a member of a mystical race fundamentally unlike the white man. A long biographical article in the Winnipeg Tribune on the morning of the 1908 Olympic marathon in which Longboat participated joked that “firewater” (alcohol) would be the only thing that could defeat him—this was yet another stereotype that alluded to alcoholism in Indigenous communities disproportionately affected by poverty.[6] While this caricaturing created even more interest in the runner by making him a familiar stock character in the public imagination, it also perpetuated stereotypes that denied Tom Longboat or any Indigenous person the full range of their personality and ambitions. These competing impulses—to accept Longboat, to celebrate him, to stress his otherness, and to stereotype him—became especially pronounced in the years of his highest-profile international races. For example, his hyped reputation and track record made him a favorite for the 1908 Olympic marathon in London, the first Games to which Canada sent an independent national team.

The Olympic marathon event in particular held great symbolic power for many observers across the Western world. The marathon was the marquee event at the Games but ultimately became one of its most controversial as well. Commentators infused the event with notions of superior masculinity and nationality; whoever won would prove which nation bred the strongest stock. The most pronounced international rivalry was between England and the United States, and while British writers (including Arthur Canon Doyle, who covered the Olympic Games as a young journalist) articulated their desire for an English victory, they indicated that any athlete competing for a nation within the British Empire would suffice as a worthy champion.[7] They did not get their wish.

At five foot eleven and 140 pounds, Longboat was especially tall and broad in the line-up of marathoners. While training with his manager, Tom Flanagan, before the Olympics in Ireland, Longboat suffered a minor injury to his knee and did not show up in London in top form. On July 24, 1908, an unusually hot and humid summer day, Longboat and a field of twenty other men left from the starting line in front of Windsor Castle and set out for the 26 miles, 385-yard course (this race established that now-standard marathon distance). Longboat took the early lead and remained in the front pack through most of the race but dropped out at around the 19-mile mark, collapsing to the ground. His trainer and doctor suspected that he collapsed from heatstroke and dehydration in the unseasonable conditions.[8] Aided by event officials, an Italian runner staggered across the finish line first after collapsing several times. Owing to their assistance, the runner, Dorando Pietri, was disqualified (but subsequently honored by Queen Alexandra for his performance) and Irish-American John Hayes won the gold medal.

Though these Olympics were not the only time Longboat would get to test his endurance against other world-leaders and reclaim his title as the greatest distance runner in the world, his failure to medal in London was part of a series of disappointments for the Canadian team, Canada, and by extension, Great Britain.

The dynamics of Longboat’s reception surrounding the Olympic marathon continued to reveal the challenges that defined his career as an athlete participating in a colonial athletic sphere. When white countrymen benefitted from national affiliation with Longboat, they embraced him as a fellow Canadian or Empire man and shared in his glory. Canadians were excited to send Longboat to London to represent their athletic prowess. When Longboat failed to meet public athletic expectations, white commentators in several nations tended to distance themselves from him along racial lines and invoke “Indian” stereotypes to explain his shortcomings. For example, newspapers reported that he was stubborn and difficult for his managers to control (without convincing evidence).[9] Other critics described his training regimen as lazy compared to his white counterparts. He alternated difficult and easy days, even walking in place of running for a low-impact workout. He admitted that he greatly enjoyed sleeping into the late morning and took advantage of it regularly. Colonizers had long projected a single version of work ethic and productivity that ignored the validity of any other approaches to labor and leisure. Rest and varied workout formats are now standard, scientific approaches to sustainable running improvement and health, but Longboat endured criticism and taunts for embracing these tactics long before they became popular, despite his regular success honed from his novel approach.

The double-standard and scrutiny extended beyond the realm of running. Despite the centuries-old push to convert North American Indigenous peoples to Christianity, church officials leveled accusations of heathenism immediately following Longboat’s 1908 baptism. The issue blew over quickly and he married a Christian Mohawk woman named Loretta Maracle only days later.[10] By contrast, commentators were usually complementary of the bride, who was a longtime practicing Christian and fit societal ideas about the intersection of proper womanhood and “good” Indigenous behavior marked by physical beauty, formal education, and familial ties to tribal leadership in the tradition of Pocahontas and ensuing Indian Princess figures. The degree to which Longboat and other public Indigenous figures fit white expectations dictated the tone of their press coverage. In so many ways, at various times in his career, Longboat was alternatively embraced and rejected by the very same entities.

After the disappointing Olympic marathon, Longboat continued to race the best known marathoners, including the 1908 Olympic podium finishers. While he had missed his opportunity to ascend to the greatest amateur athlete in the world, he capitalized on new opportunities within the realm of professional running, so that while he would lose his Olympic eligibility to complete in that safeguarded all-amateur sphere, he could perform and compete for cash prizes and regular audiences. A series of indoor races on a short track (only a tenth of a mile long) at Madison Square Garden in New York catapulted Longboat back to the highest rank of athletic celebrity. He beat Dorando Pietri only five months after the Olympic race—the two were about even until Pietri collapsed in sight of the finish line. Longboat also bested John Hayes and celebrated English runner Alfred Shrubb, with whom Longboat had a standing rivalry, at Madison Square Garden the following year. Longboat remained at the top of his sport while it remained popular into the second decade of the twentieth century.

In February 1916, Longboat enlisted in the Over-Seas Canadian Expeditionary Force. His enlistment papers defined his profession as a runner, and Longboat extended his running services to the military for messengering and entertainment. His assignment with the 180th Battalion as a dispatch runner in France mirrored historical Haudenosaunee running. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy had a long history of utilizing long-distance running for communication and mobilization beyond games and sports. In the 1763 anti-colonial struggle known as “Pontiac’s War,” for example, Iroquois runners delivered beaded wampum belts to regional Native leaders as part of their effort to organize and launch attacks on British forts.[11] This approach was similar to taken a century earlier by Indigenous runners in the American Southwest to coordinate the “Pueblo Revolt” against Spanish colonizers.[12] In fact, running trails that served as communication and transportation routes were ubiquitous across the continent before European contact. These tactics remained relevant into the twentieth century. Longboat also ran in exhibition events to entertain troops.

Longboat survived the war, but rumors of his death circulated when he was wounded in action. His wife Loretta even received official notice of his death and remarried. Longboat likewise remarried, to Martha Silverman, another Haudenosaunee woman from the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve. Together, they had four children, including a son Clifford who died in a childhood accident.

After his running career ended, Longboat worked in Alberta and a few nearby cities before moving back to Toronto where he worked as a street cleaner and garbage collector. He worked in city maintenance for many years until he retired to his home reservation.

The press continued to cover, and, in many ways, torment Longboat after he stopped racing. Journalists presented his manual labor job and duties in garbage collection as meager and lowly work instead of a stable career that allowed Longboat to provide for his family through the 1920s and 30s. Longboat himself gave an interview in 1930 in which he discussed traditional Haudenosaunee beliefs and medicine, demonstrating his knowledge of Haudenosaunee culture.[13]

Longboat died from pneumonia in 1949 at the age of sixty-two.

Two years after his death, Canada’s Department of Indian Affairs and the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada established the Tom Longboat Awards. Now administered by the Aboriginal Sport Circle, these awards recognize outstanding Aboriginal male and female athletes throughout Canada. Canada’s Sport Hall of Fame (Panthéon des Sports Canadiens) inducted Tom Longboat into its ranks in 1955. The Ontario Sports Hall of Fame inducted him in 1996. Canada Post issued a Tom Longboat commemorative stamp in 2000 that featured his Boston Marathon record time and a picture of the runner that had once circulated on trading cards.

Various running clubs and entities, the Six Nations Parks and Recreation Department as well as the community’s Health Services, continue to celebrate Longboat’s legacies across communities in organized running, the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve, and Canada. They do so by running.

– Tara Keegan, Department of History, University of Oregon

Sources:

Forsyth, Janice. Reclaiming Tom Longboat: Indigenous Self-Determination in Canadian Sport. Regina, Saskatchewan: University of Regina Press, 2020.

Kidd, Bruce. “In Defence of Tom Longboat †.” Sport in Society 16, no. 4 (2013): 515-32.

Kidd, Bruce. Tom Longboat. Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1980.

References

[1] His birthyear is disputed. Census and military records note 1886, but many other biographical sources indicate 1887. Ancestry.com, 1901 Census of Canada [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006); Ancestry.com, Canada, WWI CEF Attestation Papers, 1914-1918 [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2006). Images are used with the permission of Library and Archives Canada.

[2] “Around the Bay Road Race History,” BayRace.com, https://bayrace.com/history/.

[3] See “Boston Marathon History: Past Men’s Open Champions,” Boston Athletic Association, https://archive.is/thrTy.

[4] “Fastest Marathon Ever Run Won by Longboat,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1907.

[5] “Longboat Wins Five-Mile Relay Race,” New York Times, July 30, 1907.

[6] “History of Longboat,” Winnipeg Tribune, July 24, 1908.

[7] For an account of the morning of the Olympic Marathon race and Conan Doyle’s involvement, see David Davis, Showdown at Shepherd’s Bush: The 1908 Olympic Marathon and the Three Runners Who Launched a Sporting Craze (New York: Thomas Dunne Books of St. Martin’s Press, 2012), 3-4.

[8] See Peter Unwin, Canadian Folk: Portraits of Remarkable Lives (Toronto: Dundurn, 2013), 112-113; “Punched Longboat,” Montreal Gazette, August 8, 1908.

[9]Toronto Star journalist Lou Marsh often berated Longboat in the press. David Davis talks about additional negative press in Showdown at Shepherd’s Bush, 174-175.

[10] For example, an article from Toronto ran in dozens of papers, citing concerns about an Archbishop’s concern over Longboat’s possibly fraudulent baptism. For example, see: “Tom Longboat Married,” The Sun (New York, NY), December 29, 1908; “Longboat Weds Indian Maiden,” Detroit Free Press, December 29, 1908; “Tom Longboat A Benedict,” The Washington Post, December 29, 1908; language of heathenism circulated in this story, as well. For example, the subtitle “Indian’s Advent From Heathenism to Christianity Was a ‘Rush Job’ and Anglicans Won’t Allow It” ran in “Longboat Wooing Runs Against Snag,” The Tribune (Scranton, PA), December 27, 1908.

[11] Peter Nabokov, Indian Running (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1981), 18.

[12] See descriptions of the revolt and the role of runners in Nabokov, Indian Running, 11-13; Michael V. Wilcox, The Pueblo Revolt and the Mythology of Conquest: An Indigenous Archaeology of Contact (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 153; “Pueblo Revolt” in Rayna Green and Melanie Fernandez, The Encyclopedia of the First Peoples of North America (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2000).

[13] Mail and Empire, November 6, 1930.